Around the world, the growth of industry and consumption has escalated environmental damage through increased emissions, waste and pollution from landfills.

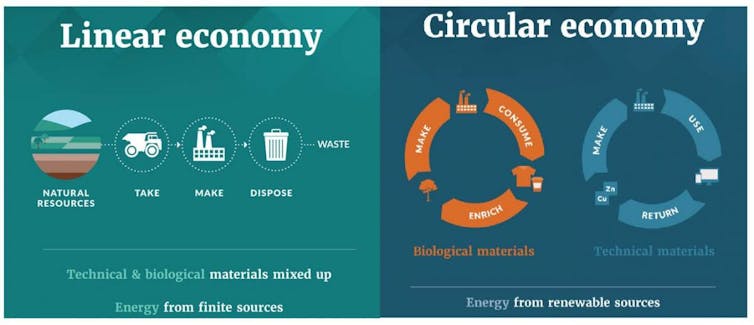

The current linear economic model, characterised by a “take-make-dispose” approach to limited resources, is increasingly shown to be unsustainable.

New Zealand’s food manufacturing industry is a major contributor to these issues. However, an alternative, more sustainable, approach exists in the circular economic model.

We have explored six large food manufacturing companies in Aotearoa New Zealand committed to circular-economy practices. We wanted to understand if and how they prioritise the four circular elements of reducing, reusing, recycling and recovering.

We identified a variety of drivers and barriers to implementing circularity. This includes consumer knowledge, government regulation, supply-chain issues and financial commitment.

Overall, we found New Zealand food manufacturers are slow to take positive steps in all areas. They lack a working knowledge of circular processes and the old linear model still holds sway.

New Zealand context

We found New Zealand food manufacturers are beginning to embrace the circular economy but there is still a long way to go for them to close the loop. The current focus is mainly on three elements (reducing, reusing and recycling), but they pay less attention to recovering materials.

In practice, reduction involves minimising the use of resources and avoiding unnecessary waste. Here the focus is on reducing the quantity of raw materials without compromising on quality.

Reusing extends the life of products and materials by finding new purposes such as refurbishing or repairing items to prevent them from becoming waste. This is especially the case with packaging materials which can be reused, recycled or composted.

Recycling refers to the process of collecting, sorting and processing materials to manufacture new products. This reduces the demand for new raw materials. For example, fruits past their use-by dates can be turned into pickles and perfumes.

Recovery extracts energy or other useful resources from waste materials that cannot be recycled. For example, withered flowers and spoiled fruits are turned into biomethane for energy production. This is New Zealand’s weakest link in the adoption of the circular economy.

Barriers to circularity

Food manufacturers told us they face multiple barriers imposed by local and offshore factors, including a lack of awareness of circular-economy principles among consumers and industry.

Research participants noted that local consumers are concerned more with price than circularity. People prefer cheaper products despite their negative environmental impact.

All companies we studied expressed this perspective. One participant said:

A major and continuing challenge for us, and our industry, is that of the single-use takeaway cup. Despite our best efforts to encourage and support our customers to sit in and enjoy their coffee, or bring their cups, we still distribute thousands of cups every year. Changing their mindset around it is still difficult.

Offshore, major trading partners in China and Japan prefer plastic packaging for their products. The food manufacturers we studied found these trading partners valued appearance and presentation first, before environmental impacts.

All companies reported being confronted with regulatory barriers. This includes lack of government support such as rebates and subsidies or robust circular-economy policies. There is no comprehensive framework on how businesses make decisions and investments.

This calls for policy revisions to help companies implement robust circular-economy practices.

Drivers for change

The COVID pandemic had a significant economic impact in slowing down the implementation of circular practices due to supply-chain disruptions. This comes on the back of transportation challenges, a lack of low-emission freight options and increases in living costs.

Based on our findings, we offer suggestions to support managers and policymakers to achieve sustainability in the food manufacturing sector.

First, policymakers can play an important role through laws, regulations, fiscal incentives, public funding and a flexible legislative framework that supports circular-economy strategies. Such measures are crucial for reducing uncertainty and encouraging investment in circular practices.

Second, we advise companies to concentrate on education and raising awareness among consumers about the long-term benefits of the circular economy. This is a much more urgent agenda than focusing on regulatory, technological or supply-chain issues. Policy and regulation change will happen in response to changing consumer preferences and patterns.

Third, because educating the public at home and abroad is not an easy fix, companies need to collaborate with each other across all parts of the food manufacturing industry, including retailers and manufacturers.

Mindsets and practices among New Zealand businesses need to shift from a linear model towards receiving training in circular-economy practices and education in sustainability and to be able to make changes for future generations.![]()

Sitong Michelle (Michelle) Chen, Senior Lecturer in International Business, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.