NZ's climate change efforts

David Hall

28 Apr 2021

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, and written by AUT Senior Lecturer in Social Sciences and Public Policy. Read the original article.

When it comes to climate change, money talks. Climate finance is critical for enabling a low-emissions transition. This involves investment and expenditure — public, private, domestic and transnational — that demonstrably contributes to climate mitigation, adaptation or both.

As New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern told US President Joe Biden’s virtual Leaders’ Summit on Climate last week:

Finance, both our financial systems and financial flows […] is at the heart of that transition [to low carbon economies].

She’s right. All the plans and strategies in the world are of no practical worth unless someone invests in the outcomes. The word “finance” means to finish, to settle, to close the deal. Indeed, finance and finish have the same Latin root in fin, the end.

Without finance, without investment, we have only unfinished business. And with official data showing New Zealand’s emissions on the rise, the need to invest in the low-emissions transition is more vital than ever.

Nature as a climate solution

In a recent report for the Biological Heritage National Science Challenge, I identified a considerable shortfall in financing for nature-based solutions to climate change.

Nature-based solutions involve working with and enhancing nature to help address societal challenges, not least the parallel crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

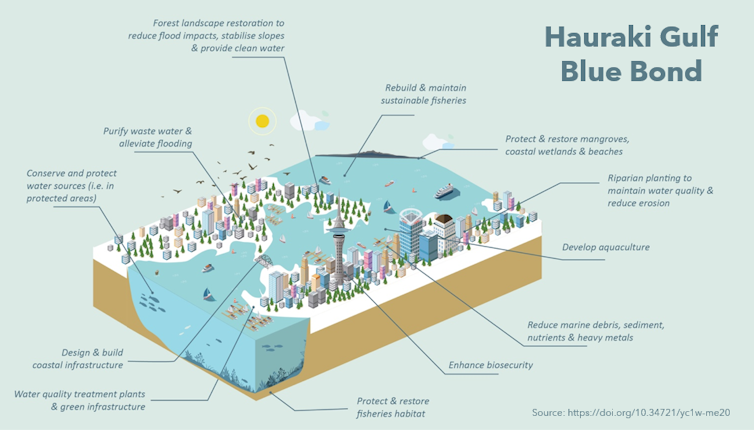

This includes forest restoration, riparian planting and urban green infrastructure, as well as enhancing wetlands, mangroves, shellfish beds, kelp forests and various other natural or semi-natural ecosystems.

Such activities not only sequester and store carbon, they also contribute to the resilience of landscapes and seascapes in a warming world. In short, biodiversity is vital for climate adaptation.

A recent analysis estimated financial flows into global biodiversity conservation need to increase five to seven-fold to meet current needs. The global financing gap is between US$598–824 billion per year.

Scaling up investment

Although no comparable analysis exists in New Zealand, there is strong evidence the same shortfall exists.

The COVID-19 recovery stimulus saw an unprecedented NZ$1.245 billion investment in nature-based solutions through the Jobs for Nature programme. But this is a one-off grant which neither reaches the requisite scale, nor guarantees long-term funding by future governments.

There are transformative opportunities for scaling up investment in climate resilience. For example, the Hauraki Gulf, a marine ecosystem that supports an economy worth at least NZ$2 billion annually, is seriously endangered by sedimentation and water-borne pollutants. This will worsen as extreme weather events become more frequent and intense.

The government could raise debt through a “blue bond” to implement the recommendations of the Sea Change — Tai Timu Tai Pari Hauraki Gulf marine spatial plan, especially through water upgrades and targeted changes to land use.

Changing the system

But this is where the issue of climate finance intersects with the broader issue of government spending. Will Ardern’s government continue with its strict self-imposed debt limit, or might “responsible fiscal management” be interpreted to include reducing the country’s exposure to climate-related risks?

After all, if prudence is the relevant virtue, then we surely fall short by leaving future generations with a fossil-dependent energy system and deficits in climate-resilient infrastructure.

Of course, the low-emissions transition should not be left to public spending alone. As the OECD has argued, private investment can create scale where constrained public sector budgets cannot. Moreover, private sector action is demanded on ethical grounds, in terms of private capital’s ability to pay, its contributions to past emissions and its gains from resource exploitation.

If capital and debt markets have a role to play, this doesn’t mean governments have no role in creating market solutions. On the contrary, the state has an integral role, not only as regulator but also as market maker.

It can play these roles well or poorly, but it cannot help but play them. The UK’s landmark Dasgupta Review details the tools governments have at their disposal to redirect the financial systems. These include taxes, subsidies, regulations, prohibitions, target setting, debt forgiveness, direct grants, technical assistance, credit enhancements, biodiversity offsetting schemes and payments for ecosystem services.

Financing the transformation

I believe a biodiversity payment is the single most effective lever to address the disadvantage natural ecosystems currently face relative to modified land uses.

Such a payment would monetise the value of biodiversity and enable communities to invest time and resources in successful restoration and conservation. This could be funded through emissions pricing, or an environmental footprint tax as proposed by the Tax Working Group.

New Zealand needs systemic change to produce an investable project pipeline in climate adaptation and nature-based solutions. Aotearoa Circle’s Sustainable Finance Forum produced a promising road map for changing mindsets, transforming the financial system and financing that transformation.

Only a few years ago, the climate finance landscape was largely bare, with only a few green shoots showing. This has since improved dramatically, with some genuine policy innovations such as making climate-related financial disclosures mandatory.

But the only real measure of success is the redirection of financial flows away from the problems and toward the solutions. We have some way to go yet.![]()

Useful Links:

- Read profile of David Hall

- Study Social Sciences and Public Policy at AUT