Kiwi kids who read for pleasure do well

Ruth Boyask, Celeste Harrington and John Milne

03 Dec 2021

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license and written by Auckland University of Technology's Senior Lecturers and Lead Researcher, Children's Reading for Pleasure Study Ruth Boyask and by Lecturers Celeste Harrington and John Milne. Read the original article.

Summer’s here and the school holidays are coming. For many parents, of course, it’s all a bit academic – pandemic lockdowns and other disruptions have blurred the line between home and school, with no guarantee things will return to normal in 2022.

The good news for parents and whānau is that relief can be as simple as turning a page. Encouraging children to read for pleasure – which is different from it being a school task – has all kinds of benefits, as highlighted in the first comprehensive review of reading for pleasure in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The review is one of three reports commissioned from AUT by the National Library as part of its Pūtoi Rito Communities of Readers initiative. The researchers looked at international and national research on reading for pleasure, finding very little on the topic in New Zealand. What research there has been has had little influence on policy.

The review’s main conclusion is that reading for pleasure is a beneficial social activity where everyone has a role to play in distributing those benefits.

Parents should feel reassured, however, that this doesn’t mean they need to be “teachers”. Simply supporting their children’s enjoyment of reading is relatively easy to do and has been shown to be very good for children’s overall development and health.

Various studies have shown children’s enjoyment of reading is related to a longer life, better mental well-being and healthier eating. Fiction reading is related to better performance at school.

But reading for pleasure is also good for communities because readers tend to be good at making decisions, have more empathy and are likely to value other people and the environment more.

Gaps in the research

We should be making more of these benefits. Because while most younger children enjoy reading in their early years at school, their level of enjoyment seems to drop off as they move into adolescence.

Time spent reading also declines as children get older. In New Zealand a lot of attention is focused in research and policy on developing children’s reading literacy at school, but there is little focus on supporting their enjoyment of reading – especially outside school hours.

There has been some attention to the importance of reading picture books and telling stories to very young children at home or in libraries. But older children and young people tend to value reading more as a functional skill that will help them with future education or employment.

There are very few well-researched studies of the reading habits and reading enjoyment experienced by children and young people beyond the school gates. Nor has there been enough research into how best to encourage them to read for pleasure.

Reading as shared experience

From our review of international literature we conclude that creating a culture of enjoyable reading needs to be approached from various angles.

One of the most important motivations for children learning to enjoy reading for pleasure comes from the people around them. When other readers share their enthusiasm for reading with children it rubs off.

Obviously this begins at home, but it can also occur in youth or religious groups, on marae, with peer groups or even online. In a major UNESCO report on “fostering a culture of reading and writing”, it’s even suggested doctors can prescribe reading together for younger parents of small children.

But while there are many good examples of people and organisations working in partnership to achieve these aims, often the focus is on improving school literacy rather than simply increasing children’s enjoyment of reading. Libraries taking a lead could change this.

Building a culture of reading

At its best, reading for pleasure is about engaging with other people in enjoyable ways – not as a solitary activity, as it is often portrayed. Practical steps anyone can take include:

* finding reading material that connects to children’s wider interests

* choosing books that more than one person enjoys to encourage discussion and sharing of ideas

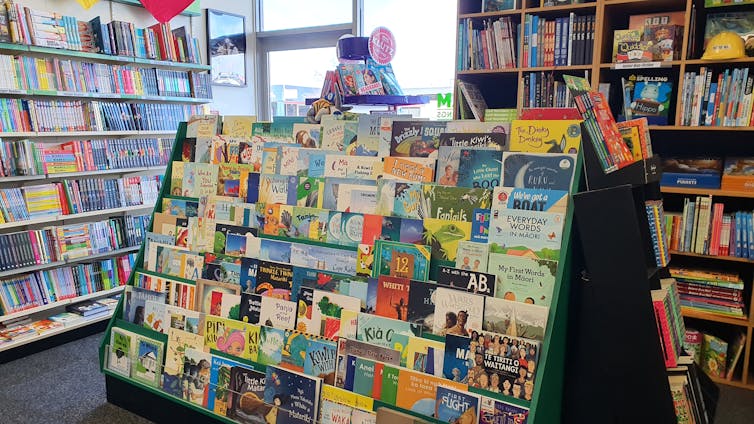

* asking librarians, perhaps from the school library, or other readers for recommendations to help find the right books

* using public libraries, including their e-book catalogues, which can be downloaded to mobile devices

* trying audio books as a way to encourage and engage readers with different reading levels or busy schedules

* encouraging discussion among peers about reading through digital and social media.

Creating a reading culture based on individual and shared enjoyment is everyone’s responsibility, not just the domain of teachers and schools. Nor does sharing the benefits of reading for pleasure mean acting like a teacher.

But it will pay dividends in improved school performance, thinking ability, well-being and sense of belonging – all especially important during these uncertain and disrupted times.![]()

Useful Links:

- Read more about Ruth Boyask, Celeste Harrington and John Milne

- Study Education at AUT