Emissions reduction plan lacks strategy

David Hall

18 May 2022

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, and written by Auckland University of Technology's Senior Lecturer David Hall, Researh fellow, Melody Meng, and Nina Ives. Read the original article.

Until now, the government’s approach to climate action has largely been about getting the policy architecture right. This work is vital, but it’s more about rearranging possible futures, less about emissions reductions in the near term.

The newly released Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) was supposed to shift gears, to get real about urgent climate action – and it partially achieves this, but only partially.

Budget 2022 will reveal some extra expenditure, but most of the $2.9 billion of climate-relevant funding was confirmed alongside the ERP. It exhibits a sensitivity to the electoral constraints on transformation, less so a sense of realism about what decarbonisation actually demands.

There are significant steps forward. Resourcing for Māori involvement in climate policy is long overdue. Integration of education and social support measures is also helpful.

In this sense, the ERP process is itself a minor victory. For years, policy scholars and public sector mandarins have championed the ideal of joined-up government, without ever doing much in practice. Consequently, the ERP is unique, even unprecedented, by taking a whole-of-government approach, weaving together all core government departments in a 340-page report.

Time to be decisive

Some of the best bits of the ERP play to this interconnectedness. Nature-based solutions – that is, enhancing natural ecosystems to address multiple challenges – emerge as a strong connective theme, not only between various sectors, but also across the National Adaptation Plan and Biodiversity Strategy/Te Mana o te Taiao.

The same can be said for planning and infrastructure which is explicit about the overlapping opportunities to reduce emissions across multiple sectors.

Similarly, the rising theme of the “bioeconomy” sheds new light on the importance of forestry, not only as a supplier of timber and carbon removals, but also as feedstock for bioplastics and biofuels to substitute crude oil.

But instead of investments to make this happen, the ERP promises a bioeconomy and circular economy strategy that won’t be complete until 2025. This is the overriding character of the document, where a large proportion of “actions” begin with the words “explore” or “investigate”, or lapse into research, baseline setting and elongated work programmes.

Even well-established ideas, such as congestion charging, are deferred. The government has investigated this policy for more than a decade, but the ERP only confirms it is “considering progressing legislative changes to enable congestion charging”.

The ERP was the moment to be decisive, one way or the other. The failure to do so leaves a lingering suspicion that the ERP’s new slew of pledges may face a similar fate.

Acceptability over ambition

So there are plans, and plans for plans, but still a shortfall of strategy. Energy sector policy, for example, takes a technology-neutral approach rather than narrowing down on priorities, such as geothermal energy, where Aotearoa is known to have natural advantages, expertise, and potential for global impact.

Such opportunities are already identifiable, even in the absence of a central energy strategy (due in 2024). Research, development and deployment take time, so strategic decisions need to be made now, rather than backloaded for later this decade.

The proposal of “climate innovation platforms” might provide the vehicle for strategic innovation, but only if properly resourced. The ERP gives an air of compromise, tending toward acceptability over ambition.

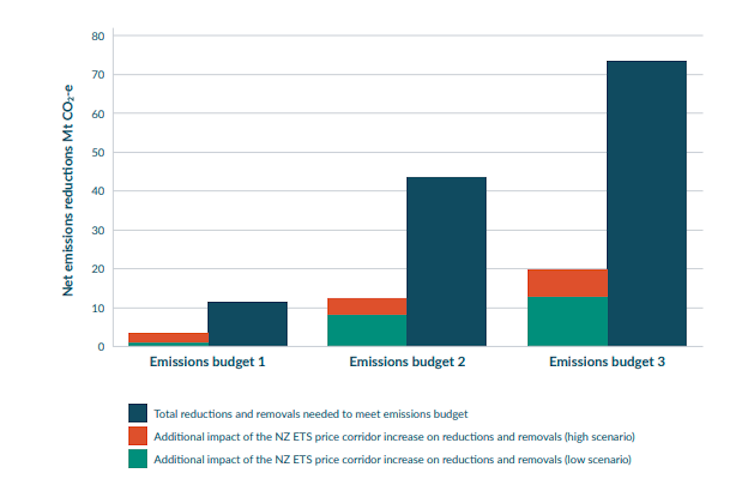

Fortunately, though, the proposed policy mix – along with an improved Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – will take us quite some way.

Emissions pricing in the ERP

The NZ$69 million Government Investment in Decarbonising Industry (GIDI) fund is being topped up with nearly $680 million, a ten-fold increase, to accelerate industrial decarbonisation.

In transport, this includes $350 million for cycleways and public transport, $40 million to decarbonise the bus fleet by 2035, $20 million to decarbonise freight transport, and $20 million for a vehicle social leasing scheme trial.

Agriculture is also the beneficiary of $710 million from ETS auctioning revenue for agri-tech and research – arguably unfairly, given that agriculture currently sits outside the ETS.

Dependence on cars

Overshadowing these initiatives is the scrap-and-replace scheme, aimed at subsidising people into electric vehicles (EVs), and already a lightning rod for controversy. The empirical record for scrappage schemes elsewhere, such as the US Cash for Clunkers programme, tends to conclude that emissions reductions are minimal despite the high investment.

Given that replacement cars must be EVs and hybrids, the New Zealand scheme may produce more emissions reductions than previous schemes did. However, the high price of EVs may mean that, even with high subsidies, low-income households cannot easily cover the difference.

Also, the scheme risks perpetuating the dependence on cars that makes transport mode-shift so elusive. Indeed, the $569 million committed to scrap-and-replace is far larger than the $350 million committed to cycleways and public transport.

It is hard to resist the conclusion that a scrappage scheme – for all the flak it will receive from efficiency-minded economists – was perceived as more politically palatable than getting people out of cars.

The political challenge

The ERP is projected to drive enough change to meet New Zealand’s 2030 Paris Agreement pledge. But part of this effort will involve the purchasing of emission reduction credits on international carbon markets, at potentially high prices.

A high reliance on paying for other countries to reduce their emissions reflects a hangover in the New Zealand government’s thinking, dating back to the Kyoto Protocol era. Deferring hard choices now by “planning more plans” might reduce the risk of backing the wrong technologies, but deferral is not without its risks either.

It speaks to the longstanding problem of treating climate change as merely a scientific, technical problem. This implies that, like any puzzle, climate action will benefit from further discovery, analysis and evaluation.

For elected and unelected officials alike, this is irresistible, because commissioning further research and strategy is a way of appearing serious, even prudent, while also avoiding vital decisions and associated responsibilities. The slow-moving quality of the climate crisis, in contrast to the fast-moving pandemic, increases the window for dawdling.

But climate action was always fundamentally about politics. The ERP practices the arts of acceptability but neglects the art of the possible – of making ambitious commitments and bringing the people along.![]()

Useful Links:

- Read profile of David Hall

- Study Social Sciences and Public Policy at AUT